Monday, March 07, 2011

Visual Reinforcement of Self-Discipline & Shedding for the Wedding

“Your wedding day should be the happiest day of your life, but what if you hated the way you looked?”

The last few television seasons have offered an influx of both weight loss/food programming (Celebrity Fit Club, The Biggest Loser, What’s Eating You, I’m Eating Myself to Death, World’s Fattest Man, World’s Fattest Woman, Heavily Ever After, Jamie Oliver’s Food Revolution, Super Skinny Me, Heavy, Man vs. Food, I Used to Be Fat, Dance Your A** Off, Ruby, Half-Ton Man, Weighing In, Freaky Eating, Too Fat for 15: Fighting Back, Thintervention with Jackie Warner) and wedding programming (Say Yes to the Dress, Say Yes to the Dress: Atlanta, Four Weddings, My Fair Wedding, Bridalplasty, Bethenny Getting Married, My Big Redneck Wedding, Bridezillas, Whose Wedding is it Anyway?, A Wedding Story, The Real Wedding Crashers, Platinum Weddings, Rich Bride Poor Bride, Tori & Dean: sToribook Weddings). What’s more surprising than the overabundance of shows dealing with weight loss, food, or weddings, is that neither of these lists is close to all inclusive.

Considering the popularity of both wedding reality TV and weight loss reality TV, it comes as no surprise that we now have a hybrid: Shedding for the Wedding (and soon, a Canadian import: Bulging Brides). SFTW asks: “What if you have the dreaded “back fat” hanging out over the top of your strapless ball gown?” or “What do you do if all those menu tastings (not to mention stress-induced snacking) necessitate letting out your dress at the seams?” While answering these questions, SFTW features 9 overweight couples competing as a team to lose the most weight, because after all, those “man boobs aren’t invited to the wedding.” And the prize for contestants subjecting themselves to America’s omnipresent gaze? A dream wedding!

SFTW positions each contestant’s inability to embody the physical ideal as the one obstacle standing in the way of their relationships and their dream weddings. In fact, most weight loss reality television programs frame being overweight or obese as the one obstacle that needs to be overcome through self-discipline in order to be truly happy. For example, if you lose weight you can: become a better father (The Biggest Loser), get a girlfriend (I Used to Be Fat), overcome addiction (Heavy), get pregnant (The Biggest Loser), lose your virginity (Heavy), get your man back (Ruby), or live happily ever after (Shedding for the Wedding). All of these goals are dependent on practicing a rigid self-control required to embody the physically ideal. These goals can only be achieved by submitting oneself to grueling six to eight hour workouts and strict diets that lead to significant, yet unsustainable weight loss in dangerously short amounts of time.

Like many makeover reality television shows, SFTW normalizes ceaseless preoccupation with physical self-improvement as a means to achieving optimum happiness and success in life. Contestants are “shamed” by being constantly subjected to the viewers’ disapproving gaze while they simultaneously internalize the notion that only physical transformation and self-discipline will alleviate further scrutiny (and, of course, their dreams will finally come true!). As contestants strive to create the “best possible version of themselves,” viewers are also invited to question whether they are adequately self-disciplining in order to ward off the same shame-infused interventions.

The majority of scholarship theorizing reality TV, specifically makeover programming, argues that television governmentalizes by positioning people as “objects of assessment and intervention” through their participation in the “cultivation of particular habits, ethics, behaviors, and skills” (Ouellette 11). However, understanding how self-governance or self-discipline is constructed or reinforced specifically through the televisual image is usually missing. We need to consider how the “disciplinary gaze” or “censorious gaze” is produced or enhanced through different choices of production. This is especially important because the power of the self-governing message on Shedding for the Wedding resides in the televisual spectacle that enhances bodily imperfection and embarrassment through costuming and camerawork. The remainder of this post is a preliminary consideration of the visual components of Shedding for the Wedding.

Introducing the Contestants. Each couple is first shown in their homes, the locations where they failed to properly self-discipline their bodies in the first place. Contestants are often depicted lounging in their living rooms, engaging in “lazy” activities (such as gaming), or depicted eating copious amounts of fattening food. The spectacle of shame begins when participants don ill-fitting, unflattering, brightly colored, spandex work-out uniforms. These uniforms are unforgiving in terms of hugging “every curve” and highlighting conventional “trouble spots,” such as “flabby arms.”

The First Work Out. The first workout is meant to to show contestants just how “lazy” and “out-of-shape” they are and punish them for their inability to self-discipline. We watch as each person sweats, turns red, cries, dry heaves, vomits, or collapses from exhaustion. The camera captures their pain and the price they’re each paying for not being in control of their own bodies. Contrary to conventional television camerawork, close-ups are limited (reserved only to depict true anguish) so that the “aesthetically deformed” bodies (Weber 87) never escape our gaze.

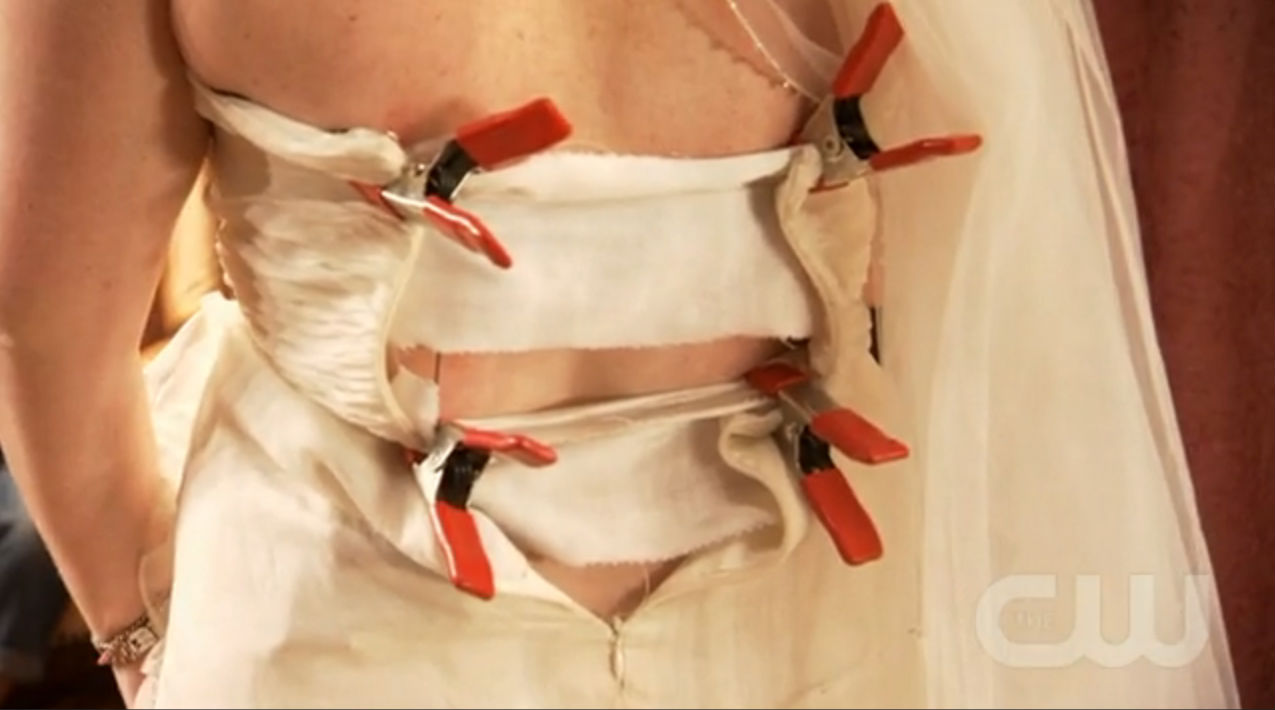

Wedding Dress Shopping (The Ultimate Humiliation). Each woman is shown trying to try on the “dress of her dreams,” yet each is unsuccessful because she is not in possession of a body that fits to the size standards set by the dress. This segment is doubly reinforcing of the physical ideal through self-discipline because sample wedding dresses are standardized in sizes 6 or 8, even though the average woman in the U.S. is a size 12. Thus, none of the sample size dresses can be closed or zipped, and the camera fixates on the apparatuses required for “undisciplined” or “shameful” bodies to wear wedding attire. One contestant is unable to get the too-tight dress off without assistance (at one point it’s wondered by the shopping attendant: “uhh, I don’t think this one’s coming off”). When the dress is finally removed, the contestant is depicted kneeling on the ground in her underwear, trying to hide her body, but still exposed, embarrassed, and forced to run out of the room to escape the camera. Ultimately, the imagery continually reinforces that while the dresses are beautiful, the bodies are not (yet).

The Weigh-In. The costuming changes at the weigh-in to maximize each contestant’s vulnerability and shame. Women are shown in sports bras while men are depicted shirtless. Many of the women stand with their hands joined in front of them, attempting to hide their bodies from the unrelenting camera, which pans back and forth across each person. During these moments of exposure and vulnerability is when the camera concentrates on their bodies most intensely. As many of the couples step on the scale, which is elevated on a stage in front of the other contestants, the camera zooms in at their thighs and slowly moves up their bodies, leaving no stretch mark, bump, bulge, or other “aesthetic deformity” unnoticed. Instead of close-up reactions shots to capture disappointment when the scale fails to reflect progress, or elation if the scale instead reflects self-discipline and #winning, the camera never moves in beyond a medium shot, always keeping each contestant’s midsection present on the screen. In fact, the only instances of the camera zooming in are to get more detailed views of the body, never the face. Instead, medium shots primarily capture the face, which are close enough to register facial expressions/emotions to create intimacy, but not so close as to remove the motivation for this show (the “unsightly bodies”) from sight or judgment.

Ultimately, the images that reinforce messages of self-governance and control over one’s body need to be analyzed in even greater detail. Regardless of the underdeveloped nature of this analysis, hopefully it draws attention to how the visual components of weight loss/wedding reality television help to create “contemptible” and “unruly” bodies in “need” of intervention.

Sources:

Laurie Ouellette, Better Living Through Reality TV.

Brenda R. Weber, Makeover TV: Selfhood, Citizenship, and Celebrity.

The last few television seasons have offered an influx of both weight loss/food programming (Celebrity Fit Club, The Biggest Loser, What’s Eating You, I’m Eating Myself to Death, World’s Fattest Man, World’s Fattest Woman, Heavily Ever After, Jamie Oliver’s Food Revolution, Super Skinny Me, Heavy, Man vs. Food, I Used to Be Fat, Dance Your A** Off, Ruby, Half-Ton Man, Weighing In, Freaky Eating, Too Fat for 15: Fighting Back, Thintervention with Jackie Warner) and wedding programming (Say Yes to the Dress, Say Yes to the Dress: Atlanta, Four Weddings, My Fair Wedding, Bridalplasty, Bethenny Getting Married, My Big Redneck Wedding, Bridezillas, Whose Wedding is it Anyway?, A Wedding Story, The Real Wedding Crashers, Platinum Weddings, Rich Bride Poor Bride, Tori & Dean: sToribook Weddings). What’s more surprising than the overabundance of shows dealing with weight loss, food, or weddings, is that neither of these lists is close to all inclusive.

Considering the popularity of both wedding reality TV and weight loss reality TV, it comes as no surprise that we now have a hybrid: Shedding for the Wedding (and soon, a Canadian import: Bulging Brides). SFTW asks: “What if you have the dreaded “back fat” hanging out over the top of your strapless ball gown?” or “What do you do if all those menu tastings (not to mention stress-induced snacking) necessitate letting out your dress at the seams?” While answering these questions, SFTW features 9 overweight couples competing as a team to lose the most weight, because after all, those “man boobs aren’t invited to the wedding.” And the prize for contestants subjecting themselves to America’s omnipresent gaze? A dream wedding!

SFTW positions each contestant’s inability to embody the physical ideal as the one obstacle standing in the way of their relationships and their dream weddings. In fact, most weight loss reality television programs frame being overweight or obese as the one obstacle that needs to be overcome through self-discipline in order to be truly happy. For example, if you lose weight you can: become a better father (The Biggest Loser), get a girlfriend (I Used to Be Fat), overcome addiction (Heavy), get pregnant (The Biggest Loser), lose your virginity (Heavy), get your man back (Ruby), or live happily ever after (Shedding for the Wedding). All of these goals are dependent on practicing a rigid self-control required to embody the physically ideal. These goals can only be achieved by submitting oneself to grueling six to eight hour workouts and strict diets that lead to significant, yet unsustainable weight loss in dangerously short amounts of time.

The majority of scholarship theorizing reality TV, specifically makeover programming, argues that television governmentalizes by positioning people as “objects of assessment and intervention” through their participation in the “cultivation of particular habits, ethics, behaviors, and skills” (Ouellette 11). However, understanding how self-governance or self-discipline is constructed or reinforced specifically through the televisual image is usually missing. We need to consider how the “disciplinary gaze” or “censorious gaze” is produced or enhanced through different choices of production. This is especially important because the power of the self-governing message on Shedding for the Wedding resides in the televisual spectacle that enhances bodily imperfection and embarrassment through costuming and camerawork. The remainder of this post is a preliminary consideration of the visual components of Shedding for the Wedding.

Introducing the Contestants. Each couple is first shown in their homes, the locations where they failed to properly self-discipline their bodies in the first place. Contestants are often depicted lounging in their living rooms, engaging in “lazy” activities (such as gaming), or depicted eating copious amounts of fattening food. The spectacle of shame begins when participants don ill-fitting, unflattering, brightly colored, spandex work-out uniforms. These uniforms are unforgiving in terms of hugging “every curve” and highlighting conventional “trouble spots,” such as “flabby arms.”

The First Work Out. The first workout is meant to to show contestants just how “lazy” and “out-of-shape” they are and punish them for their inability to self-discipline. We watch as each person sweats, turns red, cries, dry heaves, vomits, or collapses from exhaustion. The camera captures their pain and the price they’re each paying for not being in control of their own bodies. Contrary to conventional television camerawork, close-ups are limited (reserved only to depict true anguish) so that the “aesthetically deformed” bodies (Weber 87) never escape our gaze.

Wedding Dress Shopping (The Ultimate Humiliation). Each woman is shown trying to try on the “dress of her dreams,” yet each is unsuccessful because she is not in possession of a body that fits to the size standards set by the dress. This segment is doubly reinforcing of the physical ideal through self-discipline because sample wedding dresses are standardized in sizes 6 or 8, even though the average woman in the U.S. is a size 12. Thus, none of the sample size dresses can be closed or zipped, and the camera fixates on the apparatuses required for “undisciplined” or “shameful” bodies to wear wedding attire. One contestant is unable to get the too-tight dress off without assistance (at one point it’s wondered by the shopping attendant: “uhh, I don’t think this one’s coming off”). When the dress is finally removed, the contestant is depicted kneeling on the ground in her underwear, trying to hide her body, but still exposed, embarrassed, and forced to run out of the room to escape the camera. Ultimately, the imagery continually reinforces that while the dresses are beautiful, the bodies are not (yet).

Closest reaction shot during weigh-in segment.

The Body Scan

Ultimately, the images that reinforce messages of self-governance and control over one’s body need to be analyzed in even greater detail. Regardless of the underdeveloped nature of this analysis, hopefully it draws attention to how the visual components of weight loss/wedding reality television help to create “contemptible” and “unruly” bodies in “need” of intervention.

Sources:

Laurie Ouellette, Better Living Through Reality TV.

Brenda R. Weber, Makeover TV: Selfhood, Citizenship, and Celebrity.

Comments:

<< Home

This is a tough genre to say something new about, and I think you go a long way toward accomplishing that. But, I also think your background in TV and popular culture allows you to push this even further: I really like the idea of integrating the makeover TV stuff with the televisuality stuff. However, you could take Dana Heller's injunction to take the dialectical nature of popular culture seriously even further. That is, it's one thing to talk about how the contestants are represented, but quite another to analyze how the show as a whole imagines the relationships between bodies, body images, and self-fulfillment, especially the ways in which viewers emotions are manipulated throughout (Fiske's implication/extrication model). In other words, don't we at times sympathize with them, cheer for them, share in their pride and disappointment, as well as ridiculing and blaming them? SO it seems to me the show problematizes questions of body image, self-discipline, and the difficulties of changes as much as it gives us a final, consistent perspective on those issues.

Post a Comment

<< Home